Man and his creature of habit - on the power of our habits and how we can change them

"Man and his creature of habit"

Are you sometimes used to it too?

That your creature of habit rewards you

when you feed it according to its desires

far from forward-thinking diligence

but with readily available, dopaminergic, comfortably pleasurable

comfortably pleasurable mountains of stimulus

with all that the hands quickly grasp

without touching comfort zone boundaries

and at the same time there are the visions

inside us that whisper - it would be worthwhile

to educate our creature of habit

instead of fleeing back into "Tomorrow for sure!".

For when our creature of habit weighs us down

sluggish, confused, tugging at the leash

instead of walking cheerfully forward with us,

to where we already see ourselves,

it's time to grab our everyday leash

instead of letting ourselves be dragged so unconsciously

to lead us to where we would still like to be,

to birth our potentials into being.

In this way the creature of habit becomes a faithful companion

the best friend and pathfinder

is guided instead of the other way around,

and with each habit nourished anew

to get used to the unfamiliar with you from time to time

to the unfamiliar - it will reward you.

"The chains of habit are too light to be felt until they are too heavy to be broken" (Warren Buffett).

Today's article is about understanding the background of our habits, and thus ourselves, a little better. After all, it is estimated that they make up about 70% of our waking consciousness.³

What exactly is behind habits, how do they develop and how can we use them to our best advantage instead of letting them limit us, let alone determine us?

We use the term habit to describe relatively automated reaction sequences consisting of trigger, action and feedback (e.g. reward). Such habitual loops develop over time through repeated learning and practice processes and involve complex neurobiological processes. We find these habitual loops not only in the motor area, i.e. as certain physical sequences and combinations, but also in the form of thinking habits that accompany and shape us, for example, in problem-solving, either in a beneficial or in an obstructive way¹.

According to the principle "Neurons that fire together, wire together" (Donald Hebb), habits can be understood as neuronal traces - like trails that have established themselves over a longer period of time through repeated wiring of different stations in our brain.

How long this period spans is neither clearly scientifically proven, nor can it be applied to every person as a "one size fits all" rule, but can vary greatly from person to person.

For example, one study² concluded that it took between 18 and 254 days for study participants to establish a new habit to the point where it was mostly fluid and automatic. Which is not to say, of course, that at some point we cross some kind of threshold after which we no longer need to put any effort into our actions at all. Here it also depends very much on the behaviour under consideration. If it is the fingerings when playing the piano, after a longer period of time less conscious decision-making effort will be necessary than with the newly established yoga routine. After all, we are not magically and quasi-passively moved to the yoga studio on the mat at some point.

The process in which new habits become more and more crystallised involves a shift in the corresponding neuronal processes in the brain.³

While at the beginning a new habit is still connected in the area of the brain that is responsible for our language and conscious thinking (the so-called cerebral cortex, specifically the prefrontal cortex), with increasing repetition this process moves into deeper layers, the so-called basal ganglia.³

This freeing up of capacities in our front brain areas is intended to ensure that we have enough brainpower left over to be able to make conscious decisions for our life management, problem solving and goals. One could also say: for everything unusual, so to speak, neuronally unfamiliar terrain.

Imagine if this process of habituation didn't exist and they spent a lifetime driving like a learner driver, working like a first-year apprentice, talking like a toddler and living in their hometown like a newly moved in - that would certainly be quite exhausting, let alone compatible with the many other (everyday) challenges.

Our brain wants to manage its energy as efficiently as possible, and that is precisely why the habituation processes described above are so important and necessary. However, as with pretty much everything in life, there is a flip side to this coin.

In those situations in which our energy budget is already tight, so to speak, or even overdrawn (for example, when the decisions made today were already too many, the hangover and hunger too great and the sleep too little), we particularly like to fall back into our automatisms - unfortunately also into those that we actually want to discard.

"All animals in nature are out to conserve energy, and humans are no exception. This means that our behaviour always seeks the path of least resistance, which offers us the prospect of rewards at the lowest possible cost.⁴

This is exactly why willpower alone will not be enough in the long run, because these exhausted states and external stressors cannot be completely avoided in life.

In the sense of a "away from, towards" strategy (known from Neurolinguistic Programming, NLP for short)⁷, the first thing is to think about the habits we no longer want, towards those we want to build up instead.

This strategy is based on the assumption that our subconscious can process and implement positively formulated inputs better. And on the fact that our neuronal pathways cannot simply be erased, but rather are expanded via new, repeated circuitry.

So the more "alternative exits" you build into your habituated loops, the stronger your neuronal flexibility and thus your inner freedom of action becomes.

A few concrete ideas are summarised below:

1. To break old habits that are no longer desired

🌸 Create awareness:

In the first instance, it is important to precisely identify the corresponding habits and, in connection with this, also which triggers trigger the cascade of actions.

🌸 Reduce contact with environments, situations and people that bring these triggers:

So also quoted by author James Clear⁶:

"Wir werden zu einem Produkt der Umgebung, in der wir leben. Ich habe noch nie erlebt, dass jemand in einem negativen Umfeld konsequent an positiven Gewohnheiten festhält."

🌸 Create space:

Consciously creating a space between stimulus and reaction increases your self-efficacy, flexibility of action and thus freedom. For example, it can be helpful to take a few deep breaths and count down from 10 (to activate your prefrontal cortex), or to intervene through a physical action (e.g. push-ups).

2. To establish new, desired habits

👉🏻 Minimiere "Limbische Reibung":

Neuroscientist Andrew Huberman introduces and explains this term in his podcast episode on habits³:

If we optimise parameters such as sleep, nutrient and energy intake and mental balance according to our possibilities (see also 3: Booster Habits), we reduce possible inner resistance regarding the execution of our desired habits. In addition, we can design the latter according to our own fluctuations in energy levels, which for women, for example, can mean designing routines⁵ that are "cycle-appropriate".

👉🏻 Make it concrete:

If we consider beforehand when, where and how exactly we will carry out the desired actions and mentally go through this process beforehand, especially if we put ourselves into the pleasant feeling of "having done it" afterwards, we increase the likelihood of actually carrying them out many times over.

👉🏻 Reward yourself:

This can be implemented in two ways: On the one hand, we can of course reward ourselves directly after our new routine action with something that gives us pleasure and thus acts as a reinforcer for the action (according to Thorndike and Skinner's theory of classical conditioning).

In addition, we can combine the desired action at the same time with something beneficial, e.g. watching the favourite series during the home workout (so-called "temptation bundling" according to James Clear from his book Atomic Habits, 2018).

👉🏻 Break it down:

James Clear also offers the so-called "2-minute rule": Break every habit you want to establish down to a low-threshold, easy-to-implement version that can be done in 2 minutes or less (e.g.: put on running shoes). These small steps don't represent your goal plans per se, but they pave the way for them and always remain within reach without being overwhelming.

👉🏻 It's the measure that counts:

In line with the point just mentioned, it is important that we do not overextend ourselves with our habitual ambitions. For in doing so, we would achieve the exact opposite: We are overwhelmed by self-imposed demands and then tend to procrastinate, capitulate and decimate our self-worth. So before starting to initiate new behaviours, always ask yourself: Is this something that, realistically assessed, I can and want to integrate into my everyday life in a sustainable way?

👉🏻 Use external resources:

These include the people around you, who have an enormous influence on you and your behaviour⁶. For example, it will be much easier to establish a new sports routine if you often surround yourself with sports enthusiasts or even go on sports dates with them.

In addition, you can initiate people around you and ask them to support you as "control and motivational instances" in keeping up your habits.

👉🏻 “Location has energy, time has memory”:

A very memorable and apt quote from podcaster Jay Shetty, which means: Your brain finds it much easier if new habits are always performed at the same time and in the same place.

👉🏻 Stop in the middle:

This may sound very counterintuitive at first. On the one hand, it means that we can pick up the thread in a process much more quickly at a point where we left it the last time in a quite agitated and productive state.

For example, it is easier to start writing again if we do not have to start a new chapter but first finish the old one.³

Or the start of the next training session, when we have not just finished the previous one at the point of extreme exhaustion and thus stored it as a rather unpleasant experience.

3. “Booster Habits”:

These habits will help you have more energy for the day, enable creative flow and are more likely to take your other habits with you as well³:

✳️ Re-hydrate: Drink a large glass of water immediately after getting up, and of course regularly throughout the day.

✳️ UV refuelling: Grab some natural sunlight as early as possible in the morning (so-called "low angle sunlight").

✳️ Cold showers: Many hear it often, few do it often - but regular exposure to cold (especially on the back of the neck, where our brown fat sits and which has a lot to play with when it comes to thermoregulation and metabolism) has a proven positive effect on our cognition, attention, mood and metabolism.

✳️ Shake yourself: Best done in several small sessions a day - loosens up, reactivates and perks you up.

✳️ Journaling: How was your day, what encounters filled it? How did it go with the implementation of your new habits or the overwriting of the old ones? How, where and when do you want to implement them tomorrow? What are you grateful for today?⁸

Summary

If there is one thing that breaking away from old habits and building new ones requires the most, it is patience.

Sustainable change does not happen overnight, not even over a week. I would even go so far as to say that this sustainability can only be achieved when the new habits become part of our identity, rather than simply mechanical routines that we reluctantly force ourselves into. Instead of forcing yourself to read for 10 minutes every day, you become someone who loves to read. Instead of forcing oneself to go to the gym every 2-3 days under the highest inner protests, one becomes a person who cares about movement and vitality.

Accordingly, we increase the likelihood of staying on the ball if we draw long-term visions of ourselves that are as concrete as possible and combine these with stage goals derived from them. If we combine these inner resources (beliefs, visions, reflections) with outer resources (supportive fellow human beings, seminars, podcasts, apps, living space design, etc.), we are optimally equipped for our path.

And of course it will happen along the way that we stumble and fall back into old habits - we don't need to demonise ourselves for that. Register, accept and correct, so as not to further strengthen the "old paths" ("Don’t slip twice”; James Clear)⁶.

Remember also these two summary guides:

For old habits that are no longer desired (1.) - Interrupt action, incorporate reflection.

For new, desired habits (2.) - little reflection, quick action.

I think it is important not to allow oneself to reach a state of "having arrived" and well-being until one has realised one's visions.

Because with this we live in a constant state of limbo of latent discontent and drivenness, and this utopian, perfect tomorrow will probably always remain a tomorrow.

Nor is it intended to give the impression that we define ourselves only by our habits, or that we should never allow ourselves to just be and let existing habits be.

On the contrary:

I advocate accepting ourselves in the now, as and where we are, with all our existing habits, and at the same time setting out with anticipation and curiosity on the path to a future that, through the dynamics of life, repeatedly calls for course corrections through new habits. Healthy habits are a very valuable form of self-love.

And they form the solid, the holding and reliable - like a "daily energetic basic equipment" for all that is new, dynamic and creative. This is how we unite the familiar and the unfamiliar, because both need and inspire each other, and thus also us.

Poem and article: Tamara Drexler

Quellen:

¹ https://www.spektrum.de/lexikon/psychologie/gewohnheit/5939

² Lally, van Jaarsveld, Potts, Wardle (2009)

³ The science of making and breaking habits; Huberman Lab Podcast #53

⁴ Die Lustfalle - Warum Gesundsein so schwerfällt und was Sie dafür tun können; Douglas J. Lisle, Alan Goldhamer

⁶ Atomic Habits; James Clear. 2018.

⁷ https://nlpportal.org/nlpedia/wiki/Motivation

⁸ Extending the Tradition of Giving Thanks Recognizing the Health Benefits of Gratitude

Buchempfehlungen:

James Clear: Atomic Habits

James Clear: Die 1%-Methode - Minimale Veränderung, Maximale Wirkung

Charles Duhigg: Die macht der Gewohnheit: Warum wir tun, was wir tun

Douglas J. Lisle, Alan Goldhamer: Die Lustfalle - Warum Gesundsein so schwerfällt und was Sie dafür tun können

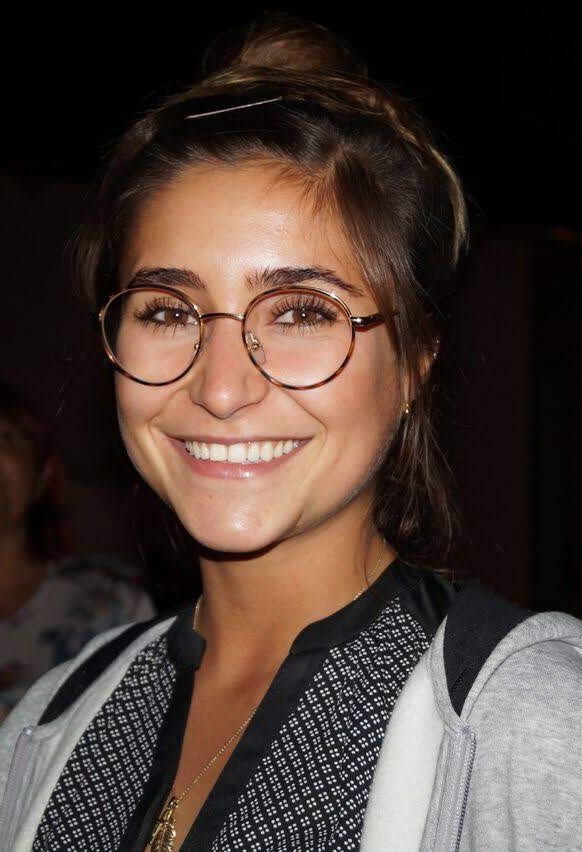

About the author

Tamara Drexler (29), a native of Passau and currently living in Berlin, is a prospective alternative practitioner for psychotherapy with a background in business administration.

After her studies (Business Administration and Economics) at the University of Passau with a semester abroad in San Diego, she first worked as a marketing manager in a medium-sized company in the region.

At the same time, there was always an inner whisper to give more attention to her enthusiasm for psychology professionally as well. This curiosity to better understand herself and her fellow human beings and to make connections led her to train as a non-medical practitioner for psychotherapy about 2 years ago.

Currently, she would like to expand her training and sharpen her focus areas through seminars, further training and internships after completing the examination in May 2022.

Professionally and privately, writing has always had a high priority as a creative channel. This includes poems (e.g. for birthdays, weddings and other special occasions), which she writes individually on request.